Everyone has a history. Good or bad, it’s our story. Having knowledge of history helps us to understand what our ancestors endured, understand other cultures, makes us better decision-makers, and better citizens. Some people are of the opinion that what happened long ago is in the past and has nothing to do we us today. I beg to differ, it is our roadmap. Unlike my brothers, I had no interest in history when I was in school. I thought it was boring. When I was studying for an advanced degree, I had to take a class in Constitutional Law. This class opened my eyes, and I began to connect the dots. We engaged in lively discussions with students of various races, regions, ethnicities, and ages. We learn and grow from past mistakes but shouldn’t repeat them. When we know better, we should do better. We are now living in the gift of the present and should look forward to an amazing future.

The main reasons for poverty occurred before we were born. Historians cite colonialism, slavery, and the caste system as causes of global poverty. With colonialism full control is gained over another country and the economy is exploited. There were unequal relationships between the colonists and the indigenous population. Approximately one half to two-thirds of white immigrates to the American colonies in the early to mid-1600’s came as indentured servants. It was a way for poor Europeans to immigrate. They worked long hours for employers for a fixed time for free. After their indenture expired, they were able to work for themselves or someone else. Sometimes, they were given plots of land. The caste system was a means of controlling the local populations. This is a system of dividing society into hereditary classes. The privileged were in a higher caste than the poor. In some societies, it is determined by birth. If your parents were poor, their off-springs will be poor.

About a year ago, I met a feisty woman who survived the Cambodian genocide. For some reason, we bonded immediately. She was a few years older than me, small in stature, and strong in might. She lived through one of the worst atrocities in history. Her husband and brother were slaughtered. Her relatives were sent to the “killing fields.” She and her three young children were forced to a labor camp. Her baby twins starved to death. She and her oldest child survived. Her eyes had seen unimaginable horrors. She and her son ate grass and worms to survive. She was forced to work from sunup until sundown in the rice fields. Her body was worn, but she had a will to survive. Even though she was exhausted, she found a way to encourage the other laborers. After the Vietnamese invaded Cambodia, she and her son eventually came to the United States as refugees. After arriving in the United States, she worked low wage jobs to support herself and her young son. They faced opposition and racism from many Americans. We both had seen horrors in our home country and experienced hunger, poverty, and racism. In spite of these horrors, she and her son rose from their past and are productive citizens. She did not have a poverty mentality or mindset. This was the bond.

My ancestors were slaves, kidnapped from their African homelands by force and put in chains. Slaves made up approximately one-third of the Southern population, and were forced to work as indentured servants, and in crop productions. The Civil War was fought between the North and South over whether slavery should be legal. President Lincoln developed a strategy to defeat the South. On January 1, 1863, he issued the Emancipation Proclamation. This document freed the slaves in the states that were fighting to keep slaves. It allowed escaped slaves to join the Army and Navy. In 1865, the 13th Amendment to the Constitution made slavery illegal. White people worried that if they didn’t own black people, they would be on equal footing. A decision was made to keep white people and black people separate. The Supreme Court supported the idea. In an 1896 case called Plessy v. Ferguson, the court said separate but equal was fair.

I and many other African Americans felt the effects of slavery for many years. I grew up in the South during times of prosperity and protest. I was the fifth and last curly-haired child born to Southern parents. My parents had three boys and two girls. As part of the Great Migration, my dad’s family moved to the North when he was a child, and settled in Chicago. He was the youngest of 10 male children born to an African American father whose parents were enslaved and a biracial mother. We learned the US census recorded her race as mulatto because she was a black and Native American woman married to a black man. It was not until years later through DNA testing that it was more likely she was white and Native American. Dad returned back to the South as an adult and met my mom. My mom was a strong-willed woman who lived all her life in the South. She was born and raised on a farm in Mississippi. She was the oldest of 10 children and born to African-American parents whose parents were enslaved. We called our parents MaDear and Dad.

Dad served in WWII as military police. According to historians, after WWll, there was a post-war boom in the economy, booming suburbs, and a baby boom. A record number of babies were born. By the time the boom tapered off around 1964, there were almost 77 million of us “baby boomers.” People were excited to have children because they thought the future held peace and prosperity. African-Americans did not benefit from the fruits of this prosperity. We continued to face the harsh realities of Jim Crow laws that kept us economically inferior and politically powerless. We continued to fight against racism and segregation. The social and political climate became turbulent and violent. Protests were commonplace. Protestors demanded passage of better civil rights legislation, elimination of racial segregation in public schools, and better wages. The Vietnam War was a source of contention. Most Americans opposed the war because they were unsure of the war’s purpose. Women began to feel dissatisfied with the simple lives they led and wanted change. African-Americans and women were living as second class citizens in a country where everyone was supposed to be equal under the law.

I learned from Dad that things were not great in non-Southern states either. As a result of the Great Migration, there was an influx of black people who settled in big cities. Lawmakers and property owners began creating discriminatory policies. Black people were living like roaches. They did not receive any type of government funding or assistance and remained impoverished. There were restrictive covenants preventing selling, leasing, or renting to black people based on race. Black people were willing to work, but without a union card, it was nearly impossible. Dad was not able to find work in Chicago because he did not have a union card. As a result, he moved back south to Mississippi with the intention of working on a farm. Discriminatory practices regarding housing intrigued me to conduct some research. Stable housing is one of the basic human needs. My family and I did not live in stable housing. There are many website articles written about poverty. I stumbled upon and read an article by Hanna Brooks Olsen, contributing writer for Everyday Feminism, January 2017. The article was insightful and mirrored my upbringing. Reading the article was an eye-opening experience and provided historical perspectives.

The Servicemen Readjustment Act of 1944 (GI bill), was implemented to give back to WWII veterans. Among other things, it was supposed to help with loans for home buyers. Black veterans like Dad and others were still being denied loans. Not much changed in their lives. They were still living in impoverished neighborhoods, invisible to society.

The National Housing Act (NHA) was developed to make buying houses more affordable. The purpose was to improve housing standards and help end crime-ridden slums. The problem was that only white people benefited. As part of this act, loan corporations created a color-coded system called Redlining to determine what neighborhoods would be viable for loans and mortgages. Black neighborhoods were coded red for high risk. Banks denied loans and mortgages because of the perceived risk. Without finances, homes, and neighborhood buildings fell into disrepair. Crime and poverty increased. White people did not want black people in their neighborhoods. The few black people who could afford to move in were threatened with physical violence and intimidation.

Eventually, the economy was doing better and many people moved from the city to the suburbs. White flight was rampant. Black people and poor whites had no choice but to live in urban areas that were defunded. White real estate investors, property owners, and land developers found a new way around anti-discriminatory policies. When I was a teenager, I witnessed white flight. We were living in public housing along with a few white poor families. There were still clandestine practices like blockbusting. This practice persuaded property owners to sell cheaply because they feared people of other races or classes would move into the neighborhood. After the white families moved, developers sold the properties to black people at double the cost. Many homes were rent to own. Black homeowners had a hard time keeping their property up because the cost was too high, and they couldn’t get loans. As a result, they lost their homes and the developers started the same scheme over. This contributed to a perpetual cycle of poverty. This practice was outlawed with the Civil Rights Act of 1968, but the damage was already done.

Earlier housing acts and laws did not help black people. Black people were at the mercy of crooked lawmakers, property owners, banks, and developers. Federal funding was available, but these crooks found ways to bypass the laws. After centuries of discrimination, the needle has barely moved. Ways were found to keep black people and poor whites in low income and segregated areas. Present-day gentrification plays a role. Historical homes and cultural centers are being torn down to make room for expensive houses. People new to the cities think these neighborhoods are up and coming. Once blacks are forced out, the cost of living increases. The neighborhoods are now no longer affordable.

Southern States passed Jim Crow laws. These laws made it difficult for black people to vote, get good jobs, or get a good education. The Ku Klux Klan (KKK), a white supremacist hate group, terrorized or killed blacks who tried to defend themselves.

It was not until the 1954 case of Brown v. Board of Education that the Supreme Court ruled that separate is not equal. Southern schools were ordered to accept all students, but this didn’t happen right away. Black people demanded civil rights, and the civil rights movement started. Religion played a major role in the planning of the civil rights movement. Many leaders of the movement were ministers. They met in churches and houses of the activists. They got their motivation to fight for freedom and equality from their religious faith. Reverend Eric C. Johnson, pastor at Mount Calvary Second Missionary Church, said “From Slavery to post-slavery, all African Americans had was a God to hold onto. They believed God was a God of justice.”

In December of 1955 in Montgomery, Alabama, Rosa Parks rejected a bus driver’s order to move to the back of the bus. She was not the first person to resist bus segregation. The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) believed she was the best candidate to lead to a court decision. A few months earlier, a fifteen-year-old teenaged girl had refused to give up her seat on a Montgomery bus. She was arrested and jailed. Her actions inspired the NAACP to use an adult in the movement, because the teenager’s actions were deemed too militant. The Montgomery buses were boycotted for over a year and resulted in the ruling that bus segregation is unconstitutional under the Equal Protection Clause of the 14th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution (Browder v. Gayle).

Many Southern states were against school desegregation. In 1957, nine black students tried to enroll in Central High School in Little Rock, Arkansas. The governor was against desegregating the schools. On the first day of school, a mob of white people gathered and began yelling derogatory names and comments to the students. President Eisenhower called in federal soldiers to escort the students to class. They maintained a military presence for the rest of the school year. Once inside the school, they were taunted by white students, and some white teachers refused to teach them. White people who wanted to help the black students were also taunted and threatened. In 1960, black college students began lunch counter sit in’s. The sit in’s started at stores in Greensboro, N.C. and eventually to Nashville, TN, and Atlanta, GA. The students were trained in non-violent protests. They chose to sit at Woolworth stores. These stores had an area to buy goods and have lunch. The students bought goods and then sat at the counter to order. The stores took their money for the goods bought but refused to serve them. They were harassed by a mob of white people. In addition to derogatory name-calling, some had itching powder poured down their backs. Others had mustard and ketchup poured on them. Many were arrested and jailed for sitting peacefully at a lunch counter. Black people and white people who wanted to help fight injustice began boycotting downtown stores. Dr. Martin Luther King participated in the boycott in Atlanta. President Kennedy and Attorney General Robert Kennedy were supportive. Stores lost business. By the next year, city officials and local businesses agreed to desegregate public facilities, like stores.

This was one of many boycotts to fight for justice. The Supreme Court ordered integration of interstate buses and bus stations. Again, Southern states ignored the rulings. A group of civil rights activists called Freedom Riders rode interstate buses in the South. This group consisted of black and white people. They were trained in nonviolence and learned tactics to stay calm. Black riders sat in the front of the bus and white riders sat in the back. At each stop, they would use each other’s waiting rooms and restrooms. Again, groups of angry white mobs gathered. Some buses were firebombed. Riders were beaten.

By 1963, buses and lunch counters were now desegregated. There was still much work to be done for equality. Public parks and swimming pools closed to avoid desegregation. In Birmingham, Dr. King started a crusade called Project C. He wanted the whole country to take notice of the ongoing injustices. Project C planned a March called the Children’s Crusade. This way, the protests could continue. The children would be arrested and jailed, instead of adults who were at risk of losing their jobs. About 950 children took part in the protest. They started with a small group initially. The children marched from parks to city hall. They were trained in non-violence and sung peaceful and spiritual songs as they walked. They were arrested when they got to the steps of city hall. More children joined the march. Birmingham firefighters were ordered to turn their hoses on the children. The powerful blast of water knocked many children down and caused injuries. They held onto each other to stand up. The police sic’d their dogs on them. Pictures of the brave children trying to walk to city hall made national news headlines. The people of Birmingham were embarrassed. City leaders agree to desegregate the stores and hired more black workers.

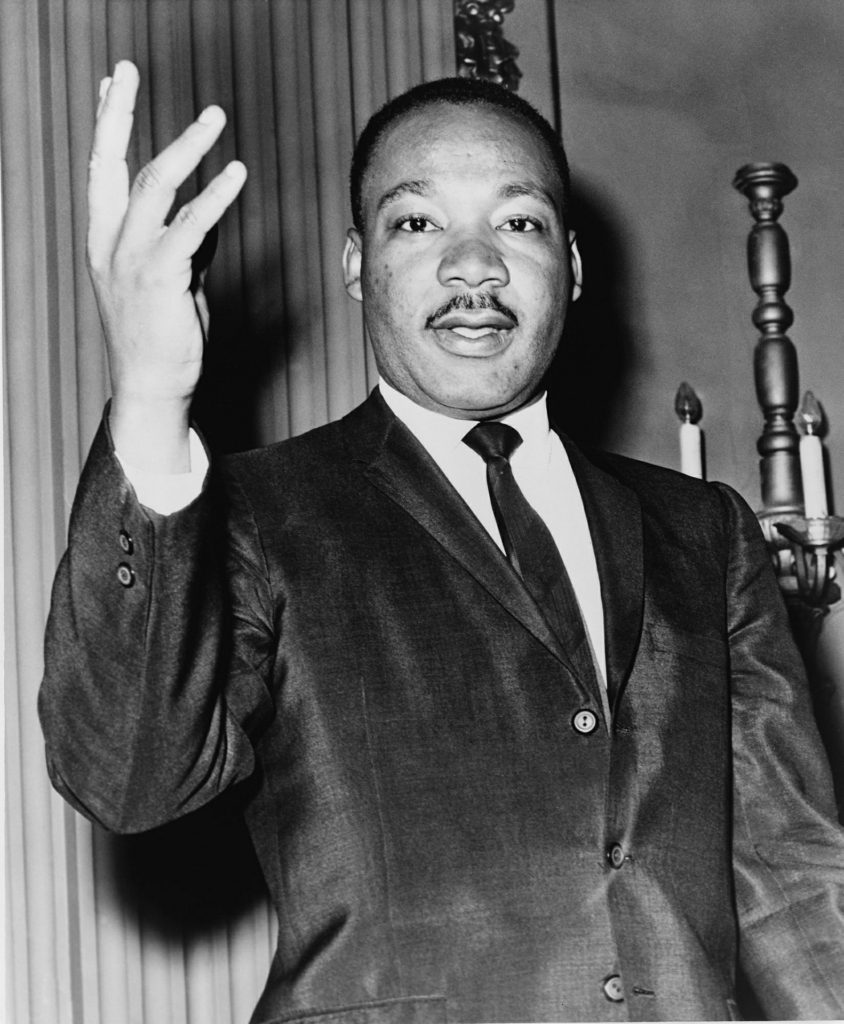

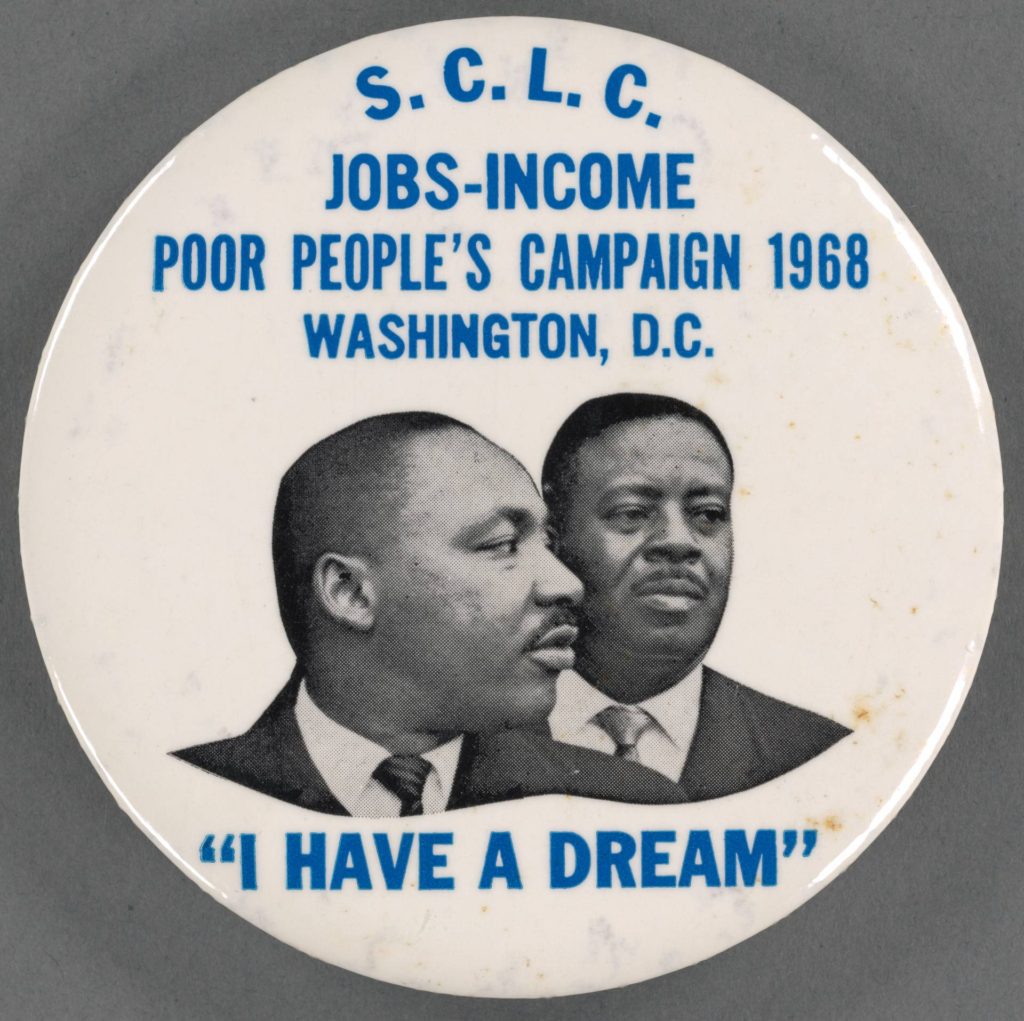

In the 1963 March on Washington, Dr. King gave a powerful speech entitled, “I Have a Dream.” Approximately 250 thousand people attended the rally. This speech was a speech of hope. Months before, Medgar Evers, a civil rights leader in Jackson, MS was gunned down by the KKK in his own driveway. The fight for justice must continue. The rally in Washington, D.C. went on as scheduled. This rally was called the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom. The crowd was amazing. White people and Black people joined together and supported the same cause. This rally helped to bring about the Civil Rights Act of 1964. This act promised equal rights to all people regardless of race, religion, gender, or national origin. In September 1963, the 16th Street Baptist Church in Birmingham was bombed by white terrorist members of the KKK. Four young girls were killed in this senseless act of violence. There were other injuries. In November 1963, President Kennedy, a supportive of equal rights for all, was assassinated. I remember exactly where I was when I heard this awful news. We were all in shock.

You would think by now, Americans got it. Unfortunately, this was not the case at all. Many Southern whites continued to resist change. State and local laws were still being used to segregate society. One area of continued injustice involved voting. Jim Crow laws made it impossible for most black people and nonwhites to vote. They were arrested if they tried to vote. They were given unfair literacy tests and had to pay poll taxes. Literacy tests were created by government officials, and the results were rigged by biased and racist registrars. The registrars were the sole judges and it was their opinion if a person passed or failed. Many college educated black people failed, while illiterate white people passed. Whites were often excluded from taking it, if they were of good moral character. These taxes were levied on people regardless of income and were passed in an effort to keep black people and other people of color from voting. Fannie Lou Hamer was a plain spoken and strong civil rights activist from Mississippi. She was the organizer of Mississippi’s Freedom Summer. She learned about the constitutional right to vote and actively engaged in the civil rights movement. She was jailed and beaten, but she continued on in the fight. In 1964, she helped co-found the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party in order to give black people a voice. She traveled across Mississippi registering people to vote. Three volunteers were killed. In 1964, she and other activists traveled to the 1964 Democratic National Convention as a representative from Mississippi. President Johnson signed into law the voting rights act of 1965. This act was meant to overcome legal barriers at the state and local levels that prevented black people from voting.

In March 1965, civil rights leaders planned a march from Selma, Alabama to Montgomery, Alabama. State troopers told them to turn around, but they didn’t. The non-violent marchers were attacked with clubs, whips, and tear gas. Because of the violence, this was known as “Bloody Sunday.” This march helped bring about the voting rights act of 1965. This act stopped the literacy tests and outlawed taxing voters.

In 1966, Dr. King helped organize the Chicago Freedom Movement. In Chicago and across the country many realtors would not sell homes to black people. This movement led to the Fair Housing Act of 1968. The civil rights movement helped African-Americans move into positions of power. In 1967, Thurgood Marshall became the first African American Supreme Court Justice. More African Americans were in various positions to help and be a voice for equality and justice.

In 1968, Dr. King came to my hometown of Memphis, Tennessee to support the sanitation workers. After years of poor pay and dangerous working conditions, black sanitation workers met and agreed to strike. Two workers were crushed to death from a garbage compactor. The city refused to replace the defective equipment. The striker’s slogan was “I AM A MAN.” The mayor of Memphis declared the strike illegal and refused to meet with local black leaders. Memphis had a long history of segregation and unfair treatment of black people. A former corrupt politician, E.H. Crump was a dominant force in the cities politics for most of the 20th century. He was referred to as “Boss” Crump. His influence still dominated the city. We heard that Dr. King was coming to town to help. The excitement was in the air. Prior to the strike, he spoke to an audience of thousands. A demonstration turned violent when protestors started breaking windows. The police responded by beating the protestors with batons and using tear gas.

A sixteen-year-old boy was killed. Following the funeral, sanitation workers marched peacefully downtown. There were still concerns about race riots. Dr. King was assassinated on April 4, 1968, while standing on the balcony of the Lorraine Motel in Memphis. Again, it seems like the world stood still and was in shock and disbelief. His assassination intensified the strike. The mayor feared rioting. On April 8, 1968, Coretta Scott King, Dr. King’s widow, organized a completely silent march. About 42,000 people participated. The strike ended on April 16, 1968, with a settlement for increased wages and union recognition. The city did not honor its agreement until additional strikes were threatened. One week after Dr. King’s death, President Johnson signed the Civil Rights Act of 1968. It was also called the Fair Housing Act. This act stated the sale and renting of houses must be fair and could not discriminate based on race, color, or gender. In June of 1968, U.S. Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy was assassinated. Not again! Powerful leaders who were in a position to help black people and poor people were gunned downed in cold blood. Many people were fearful and felt helpless.

In the late 1960’s many non-violent activists were worn out due to the constant threats of danger. They saw that non-violent actions were in-effective against violent whites. New leaders evolved. I was a young teenager during this time and living in a housing project within walking distance of downtown Memphis. I joined in the marches for equality and against injustice. With raised right fists, we shouted “Black Power” as we marched down the city streets. Our white teenage counterparts did the same. The police glared at us, ready to pull the trigger. We didn’t feel marching was enough, and we didn’t want to be killed. We looked for other opportunities to protest. At my high school, the female community activist student leader spearheaded a committee called Black Monday. Every Monday, we boycotted classes. Other high schools joined in. This continued until we were threatened with suspension for missing too many days out of school. We didn’t know how to boycott. Prior to each boycott, the civil rights leaders were adequately trained. We did not have this type of leadership and abandoned our campaign. We committed ourselves to continue our education so we could be in a better position to affect change and get out of poverty. This was how we were going to make a difference.

There is a saying that you don’t know what you don’t know. Many people do not know the history of systemic poverty and racism. The playing field was not level. We do not live in a society that rewards hard work equally. Knowing what previous generations endured and growing up during the civil rights movement, made me a stronger and more knowledgeable person. I owe it to my ancestors and myself to live a life they fought so bravely for. As a result of the civil rights struggle, we should embrace each other’s culture, and we are empowered to make a difference. Part of that difference is supporting each other as we do our part to tackle the struggle of poverty.

References

Adamson, Heather. 2009. The Civil Rights Movement. Mankato, MN. Capstone Press.

Aretha, David. 2008. The Civil Rights Movement. Selma and the Voting Rights Act. Greensboro, N.C. Morgan Reynolds Publishing.

Terp, Gail. 2016. Non Violent Resistance in the Civil Rights Movement. Minneapolis, MN. Abdo Publishing,

Goshay, Charita.” Religions Role in the civil rights movement”. August 31, 2013. Accessed October 4, 2019.

Olsen, Hannah Brooks. “Why Escaping Poverty Isn’t Nearly as Easy as People Think”. January 29, 2017. Accessed September 27, 2019.

Weiss, Alan. “Moving from a Poverty Mentality to an Abundance Mentality”. Accessed September 27, 2019.

“Indenture Servitude”. Wikipedia. Accessed October 7, 2019.

“Caste”. Wikipedia. Accessed October 7, 2019.

Copyright © 2020 Francie Mae’s Journey

Keep on writing, great job!