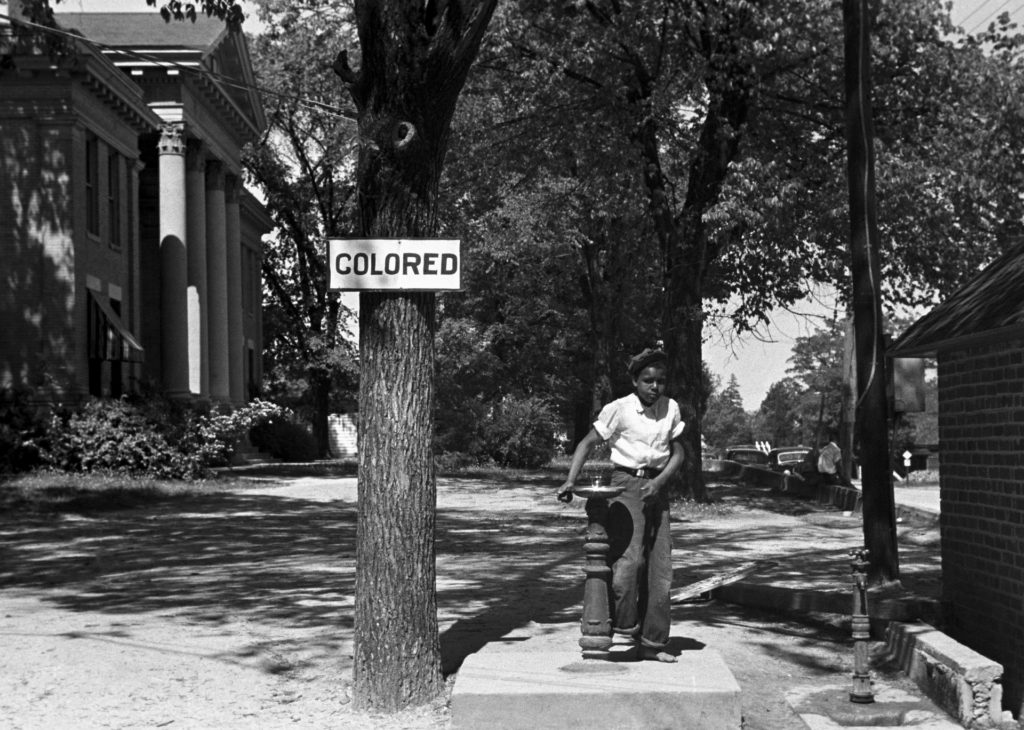

The South was called the Dirty South because of the way black people and other minorities were treated. Black people had separate water fountains, separate access to schools and facilities, limited opportunities such as housing, medical care, education, employment, and transportation. I never understood how discrimination is allowed in the United States and supported based on skin color. As a child who always asked why, I tried to connect the dots, but they didn’t connect in the dirty south.

My family and I were economically poor but not poor in mind or spirit. My God-fearing parents made sure of that. My four older siblings were born at home in north Mississippi and delivered by midwives. Midwives were women in the area who delivered babies. Unlike midwives of today, they had no medical training. We all had nicknames that were given to us by our parents. My given name is Frances, but MaDear chose to call me Francie Mae. I think it was because I asked so many questions, and when she wanted me to stop; she wanted me to know she meant business. This was my warning. I don’t know where the Mae came from but it stuck.

As mentioned previously, Dad and MaDear grew up in different regions of the country. MaDear knew a life of farming and Dad did not. Growing up in the city of Chicago, he learned a skill as a bricklayer. He played football, was studious, and enjoyed learning. His parents died when he was young, and he was raised by relatives. He had to drop out of school in the 11th grade to support himself. He married later in life. His brothers were deceased by the time he married and had children. He was a slightly built but strong caramel-colored man with curly black hair, and light brown eyes. When he was younger, he wore his long hair in a ponytail. When he moved South, he had to cut that ponytail! He was a smart man, talkative, and loved to write letters to the editor. Some of his letters were published in the local newspaper. I felt something was missing because I never met my paternal grandparents. There were no pictures of them, but there were pictures of Dad, my uncles, and other relatives. They were all dressed nicely in suits and looked distinguished. Their curly black hair was perfectly coiffed. There was a history behind the pictures. I pressed Dad for my information about his parents. His answer was he was young when they passed away, and he didn’t have much to share. He always told the story that his mother was half black and half Native American. Later, we learned her ancestry was a well- kept secret, since she was actually white and Native American. His parents had to escape from Mississippi because they had a mixed-race marriage.

MaDear was a dark-skinned, strong-willed, stoic, wise, and no-nonsense country girl. She was a woman of few words, but when she spoke, you paid attention. Her parents were descendants of slaves and were farmers. She was notorious for wearing a scarf on her head called a “head rag.” This was part of her African ancestry. She didn’t get dressed up unless she went out visiting or to church. She only completed the 6th grade because she had to work on the farm and help care for her younger siblings. Plus, Mississippi schools only went to the 6th grade. She took on a mother’s role at an early age and didn’t let anyone walk over her siblings or her children. She was the strongest woman I knew. One of her sisters passed away in childbirth before I was born. The brother close to her in age was drafted and served in the Army during WWII. After he came home, he went missing for many years. Eventually, he was found in another state. During those times, military people who went missing were referred to as being “war-affected,” or “shell shocked.” Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) did not have a name, nor was it treated, during those times. Her sisters and brothers also had to quit school at an early age and help out on the farm. They all had a strong family resemblance. As young adults, there were pictures of all the siblings except MaDear. She never liked to take pictures. They were also dressed in their best and smiled and profiled proudly for the camera.

My maternal grandparents were called “Momma” and “Poppa”. Their parents were both slaves. According to the 1920 U.S. Census, Poppa and Momma were born around 1885 and 1894 respectively. Since they didn’t have birth certificates, they had to guess. Sometimes parents wrote their children’s birth dates in the Bible. This was considered legal documentation. Momma and Poppa both passed away when I was young, but I remember them both. Poppa was a kind, tall, slight man, who wore overalls and work shoes. Momma was a kind, short, round woman, with a big smile. She was a great cook and always wore an apron over her dress. I never saw her without a headscarf. She wore it wrapped from the back of her head to the front and tied it with a perfect African knot.

I was too young to remember all the details of their life. My two oldest history buff brothers had remarkable memories and became family historians. Momma and Poppa were not sharecroppers. They rented their land from a local businessman. Even though both grandparents were hard workers with a “can do” attitude, their education was limited. None of their children finished school because of Mississippi school laws, and they had to help with the farm work. In 1954, John Deere tractors were introduced to the farmers. In order to continue renting, the landowner insisted they had to mechanize. This was a way to produce more crops. This was a new innovation that Poppa was not familiar with. He wanted to stay with the familiar way of farming. He and Momma were not able to read, and their children did not read well enough to understand the legal documents. They lost their farm and had to start over by sharecropping.

Dad’s uncle lived on a farm next to Momma and Poppa. This uncle was his father’s brother. He passed before I was born. Because of the Davis-Bacon Act of 1931, Dad lost his job as a bricklayer. This act required private contractors to pay prevailing wages (hourly wage, benefits, and overtime) to all employees on construction projects. This sounded like a good thing in theory, but the act prevented non-unionized black and immigrant laborers from competing with unionized white workers. Most of the major construction unions excluded black people. Dad was not able to get a union card, and his economic opportunities were restricted. In an effort to support himself, he moved back South to live with his uncle and work on the farm. It was on this farm that he met my mother.

After marrying, Dad was drafted and served in the Army during WWII as a Military Police. He was stationed in Arizona and saw a different way of life. He wrote many letters home to MaDear. She saved most of them in her treasured footlocker. I had the opportunity to read his letters years later. His penmanship was unusual. We later learned it was, or similar to Spencerian script, a style of writing he learned in Chicago. He also sent pictures of him dressed smartly in his Army uniform, his light brown eyes shining brightly beneath his hat that was always slightly cocked on his head. His eyes represented hope. In his letters, he encouraged MaDear to stay positive and trust God. If he was concerned about how he was going to provide for his family after he was discharged, it was not written in his letters.

After discharge, Dad returned to Mississippi and he and MaDear began their family. Reality hit hard. This veteran and military police was not able to get employment. Dad had three strikes against him. He was an intelligent and smart black man, he was raised in the North and did not share Southern ideologies, and his appearance was different. Our life of poverty began. Dad never wore overalls and enunciated his words when he spoke. He insisted that we speak in the same manner. He believed in discipline but not by spanking or with a switch. He didn’t grow up that way. He believed the best way to discipline children was to have clear and consistent rules, and explain the consequences if we misbehaved. The few times we were disciplined by spanking or switch were by MaDear. Even then, we knew the reason why. Dad believed that we could show respect to adults without saying “Sir or Ma’am.” It was okay to say “Yes or No” when responding but never What? I think saying “Sir or Ma’am” reminded him of being subservient and had racial overtones from slavery. Many black adult men and women had to cast their eyes downward and say “Sir or Ma’am” to white people of all ages.

Prior to my birth, our family moved from northern Mississippi to Memphis. MaDear and Dad wanted the best life for us. Tennessee had compulsory school laws and Mississippi did not. They realized the importance of education, and they did not want us to miss school to work on farms. I was the only child born in a hospital. During those times, all black babies were born in the same hospital. There were limited employment opportunities for black people. My parents moved around a lot in an effort to sharecrop. As kids, we used to tease and compare Dad to Eddie Albert on Green Acres. Being the city slicker he was, he knew absolutely nothing about farming. Since he never wore overalls, this didn’t help. We moved around from shack to shack, each one worse than the previous one. My eldest brothers told me that sometimes we moved by horse and wagon. They said we used to duck down so no one would see us. Their friend’s parents had cars. It was not the horse and buggy days, but we were lucky if we could borrow the horse and buggy. They told me I learned to wrestle at a young age. When I was two, I wrestled with the family dog over a bone. We were both hungry. I got the bone, but the dog bit a plug in my head that left a permanent scar. My brothers said they never saw the dog again after this incident. We never had a family dog again. There was not enough food for us and a dog. After this, it was time to move again.