In the book by C. L. Lincoln, The Negro Pilgrimage In America, slaveholders rejected both Biblical and political arguments. They used the Bible to “prove” justification of slavery by identifying black people of Ham, forever ordained to be “hewers of wood and drawers of water.” They argued there was a historical justification for slavery. Wealthy and political Southern white men saw slavery as a benefit and provided economic security. The Declaration of Independence doctrines were interpreted by the South as not apply to slaves because they had no part in the framing and were considered to be a “lower order of beings.”

The slave system grew out of plantation life. The plantation was described as an organized community, the administration rested in the hands of the owner or, in the majority of cases, a head overseer. The center of the plantation was the owner’s home. Next were the overseer’s home, the stables, smokehouses, corncribs and other storage areas. The slave quarters were located nearby. They were described as one room huts with earthen floors. Often enslaved people were denied sufficient food and clothing. Pregnant women were forced to work in the fields and many were unable to bear healthy children.

Many churches ignored the conditions under which the slaves lived, however, the Unitarians, were consistently anti-slavery. This denomination believed in the worth and dignity of every person. Lincoln wrote that many Southern churches upheld the practice of slavery. The Methodist church initially attacked slavery as a moral blight upon America. By 1836, they changed their position by stating they had no “right, wish, or intention of interfering in the civil and political relations between master and slave as it existed in the slaveholding states of the Union.” Many Southern ministers devoted much of their time writing pamphlets and lecturing on the alleged inferiority of black people. Around 1844, the tension within religious organization reached a dramatic point. The Baptists divided over sending slaveholding missionaries into the expanding Southwest. The Methodists split over whether one of their ministerial officers could hold such a high office and retain the slaves he acquired.

Lincoln wrote “Slave Codes dealt with all facets of slave live, from barring of private meetings (none were permitted unless a white man was present) to prohibition against entering into or maintaining legal contracts. Violation of the Codes was punishable by penalties ranging from whipping to branding. As the money from cotton became more important, slaveholders generally refrained from administering punishments that would leave a slave permanently crippled. The breaking of Negroes on the wheel was replaced by merciless floggings. Sometimes more stubborn slaves were burned to death at the stake. Escape was the most serious offense, and often punishment was meted out on the spot if an escaped slave were captured.”

According to Lincoln, eventually there was a westward expansion of the United States and the issue of slavery continued. The portion of the Louisiana Purchase that became the Missouri Territory sought admission to the Union as a state. Because so many of the white inhabitants came from the South, it was assumed that Missouri would join the Union as a slave state. When Alabama joined the Union in 1819, there was a numerical balance in the Senate between slave and free states. When Maine tried to join the Union in 1820, Southern politicians were forced into a compromise. The separate bills sponsoring Maine and Missouri were combined into a single measure. Under the compromise, slavery would not be prohibited in the Missouri state constitution. The liberals were able to promote one important stipulation. Congress required a pledge from the Missouri legislature that its new constitution would not abridge the rights of United States citizens. This means the freedoms of freedmen living in the state were protected.

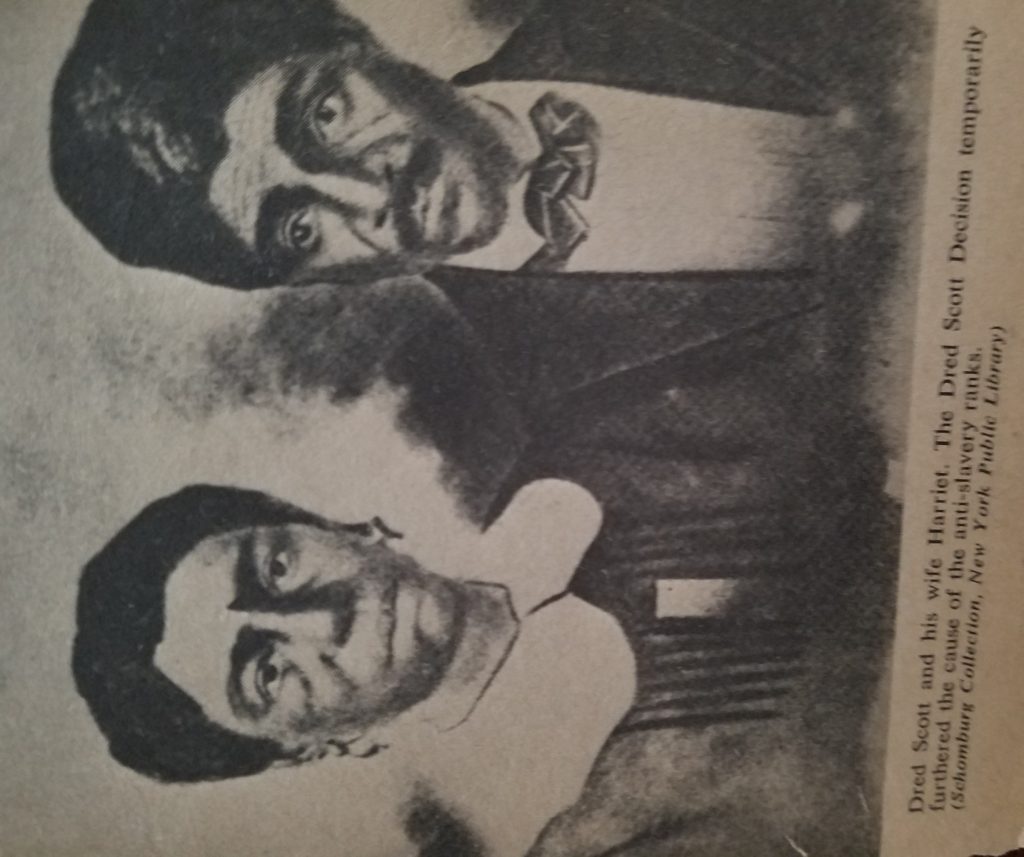

This leads to the Dred Scott decision. In 1834, Dr. John Emerson, a U.S. Army surgeon, and his wife moved from Missouri to Illinois. They took with him, Dred Scott, an enslaved man. Previously, he lived with the doctor and his wife in another state, married and began raising a family. They all returned to Missouri in 1838. After the doctor died, Mr. Scott sued the doctor’s wife for his freedom on the grounds he had lived in free territories that ended his bondage. By this time, Dr. Emerson’s widow, had remarried. Her new husband was a prominent abolitionist and Congressman. Together, they developed a plan to help Mr. Scott. The plan was to get his case into a Federal court and hoped there would be a favorable decision. This would create a precedent allowing other slaves to gain freedom with the backing of the judiciary. To avoid the Congressman from appearing in court as a defendant slaveholder, Mr. Scott was technically “sold” to the Congressman’s brother. The case was heard in several lower courts before reaching the U.S. Supreme Court. With Southerner’s dominating the Supreme Court, the Chief Justice handed down a decision that proclaimed slavery was a national concept. He ruled that black people did not come within the meaning of the Constitution’s “people of the United States.” The Court ruled that a black person had “no rights which a white man need respect.”

The Civil War was next in the long road to justice for black people in America. In 2021, we’re still traveling this road to justice. We need to know history, political positions of politicians, and vote for candidates who are committed to justice and equality.

Francie Mae. April 17, 2021

Reference

C. Eric Lincoln. November 1967. The Negro Pilgrimage In America. Bantam Pathfinder Books.