Beale Street is a colorful street in downtown Memphis, Tennessee. When I was a child, because of legal segregation, it was the only street where Black people could shop. In return, Black people made the street their own. It was more than a collection of saloons, stores, pawnshops, lodge halls, lawyer’s offices, insurance offices, and doctor and dentist offices. Many businesses were owned by Black people.

The beautiful Beale Street Baptist Church is a historic church on the street. It was built by freed slaves. The Gothic style church was constructed between 1871 and 1885. It was also important in the early civil rights movement. In the late 1890s, Ida B. Wells, the famous civil rights activist and journalist, housed her newspaper, The Memphis Free Press, there. The newspaper was later destroyed by a white mob. The church was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1971.

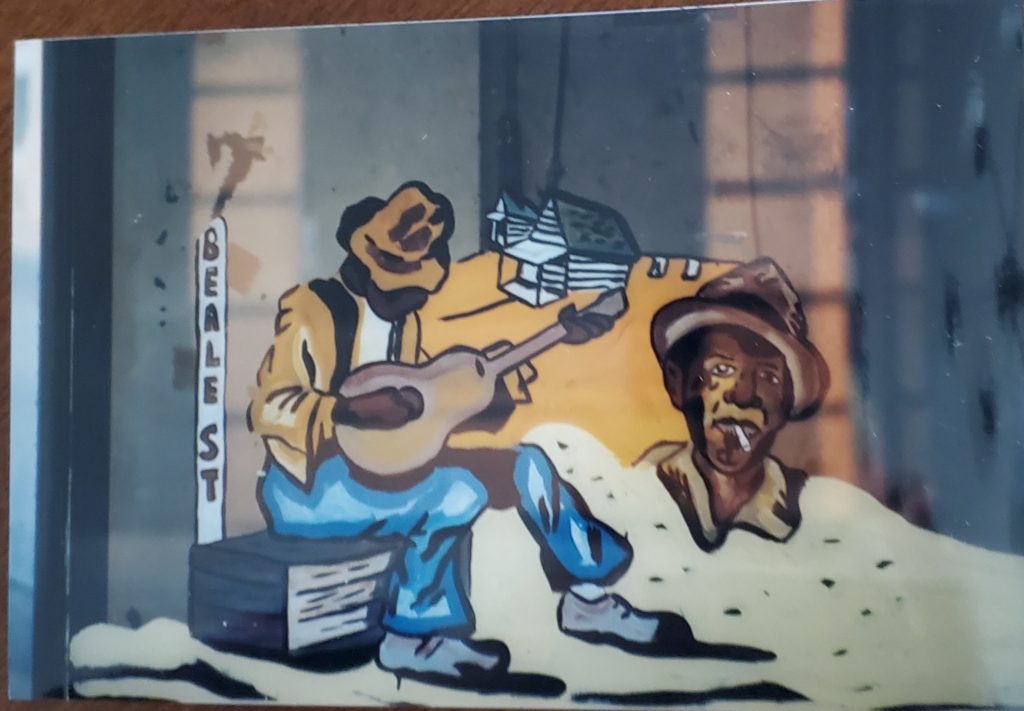

Beale Street was special and Dad never failed to tell us its history. Beale Street was created in 1841. In the 1860s many Black traveling musicians began performing and playing in the clubs. These blues and jazz musicians helped develop the style known as the Memphis Blues. Handy Park was named after a Black bluesman, W.C. Handy. It was one of the most economically viable Black neighborhoods in the country.

Beale Street was both a main street and back alley street. Gamblers, heathens, hypocrites, harlots and church people graced the street. There were professional men in their black suits, as well as country people in overalls and plain dresses. Pimps wore their Stetson hats, silk shirts and diamond stickpins in their suits. Itinerant preachers stood on the sidewalk or in Handy Park, shouting their own hell-fire-and –brimstone blues. There were con men and voodoo and hoodoo women. People of all ages danced to the music of the wandering musicians. Beale Street was a place where Black people from all walks of life could gather, shop, handle business, and have fun. This was a street where every Black man, woman, and child was welcome. Most people visited Beale Street but never patronized a saloon, gambling den, or other non-business areas.

Years earlier, in the 1870s, there were a series of yellow fever epidemics in Memphis. Thousands died and thousands more left. Whites were more vulnerable to the disease. Many immigrants from the British Isles and northern Europe had no natural immunity to tropical fevers. Black people seemed to have some resistance. Only 20,000 people remained in the city. It is estimated out of the 14,000 Blacks who stayed, 900 died. Of the 6,000 whites who stayed, 4,000 died. The city lost its charter because the citizens were fleeing and no income was coming in. Some people wanted to burn the city to the ground. Memphis was able to clean up and after twelve years as a taxing district, it was able to recoup enough to offer a bond issue as the first step toward regaining its charter. The first man to step forward to purchase a bond was a Black man, Mr. Robert Reed Church.

Church was the son of a white steamship captain and mixed race mother who was owned by his father. She died when Church was around twelve. As a child, he worked on his father’s riverboats. In 1862, federal troops commandeered his father’s boats after a brief naval battle on the Mississippi River. Memphis was in the hands of the Union and young Church got a job in a saloon. He went on to gain a fortune in real estate.

Church purchased land around Beale Street. He became the first black millionaire from the South. He was a leader in the black social circle, but his close friends included some of the upper crust of white Memphis society. Despite Jim Crow laws, he dined with them in restaurants and on trains. His wife was described as a “belle in colored society.” They built and lived in an elaborate thirteen –room house near Beale Street.

In 1890, Beale Street underwent renovation and the Orpheum theatre was added. Later, Church paid the city to create Church Park, located at the corner of 4th and Beale. The auditorium became a gathering place for musicians to gather. According to historians, Church Park had an auditorium that could seat around 2,000 people. Speakers included Booker T. Washington, President Woodrow Wilson, and President Franklin D. Roosevelt.

Near the turn of the century, Memphis had recovered from the devastation of the epidemic. By 1878, it became one of the South’s fastest-growing cities. The population was 100,000 and included 49,000 Black people. There were no parks, playgrounds, or recreational activities until Church opened his par and auditorium. It was the center of social life for most Black Memphians. For years, it was the only place where Black entertainers could perform for Black audiences.

Many out of town musicians traveled to Memphis and played on Beale Street. One was the talented Mr. W.C. Handy. In 1902, he and his band traveled throughout Mississippi. They made frequent trips to Memphis and around 1909, decided to make it their home. There will be more on Handy and Beale Street in the next blog.

Francie Mae. September 10, 2022.

References

Beale Street. Wikipedia. Web. Accessed September 10, 2022.

McKee, Margaret and Chisenhall, Fred. 1981. Beale Black & Blue: Life and Music on Black America’s Main Street. Baton Rouge. Louisiana State University Press.

.