Memphis’s first mayor, Marcus Winchester, was intriguing to many people outside of Memphis. Because he married a “free woman of color,” he became the leading attraction of visitors to the river city, especially those of the radical or reformer type

One such lady, identified as Mrs. Ann Royal, visited Memphis frequently. She and many others called the former mayor, Major Winchester, in reference to his military rank. She thought he had an interesting family and credited him for rising above caste and prejudice. He was hailed as a “free soul.” Major Winchester was flattered by the attention from one of the country’s most brilliant reformers. Her views, considered radical in those days, about the color line gave him consolation for marrying the woman he loved.

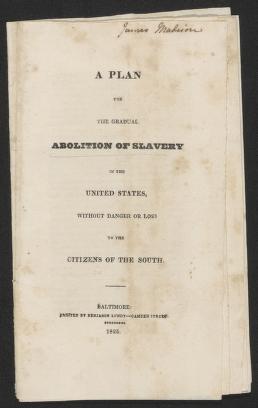

In 1825, another lady in man’s hat came to Memphis. She had read a book entitled, A Plan for the Gradual Abolition of Slavery in the United States without Danger of Loss to Citizens of the South (Baltimore, 1825). She was an eccentric friend of Major Winchester and was named Frances (Fanny) Wright. She traveled to Memphis to visit.

This wealthy woman was born in Scotland but toured across America. She was an author of a book entitled, Views of Society and Manners in America (1821). She found the United States was the land of her political dreams. Her ultimate goal was to help abolish slavery. She and a fellow emancipationist, George Flower, travel to the South to find a site for her project. They arrived in Memphis on October 8, 1825 and bought many acres of land .It was called Nashoba, a colony near Memphis. This colony is the present day Neshoba, near the present day Germantown.

By March the next year, two log houses had been built and some land cleared. There, Fanny assembled her relatives, friends, and enslaved people on the land. Her plan was to educate the enslaved Black people and free them when their combined labor earned $6000 plus 6% interest. Afterwards, she planned to send them to South America as independent farmers. For months, she and her companions worked hard on the land. They piled brush and rolled logs from early dawn until dusk. She came down with malaria and other diseases. Because of her health, she had to return to Europe.

She left the care of Nashoba in the hands of her sister, Camilla Wright. She and others hired by Fanny were inexperienced. They lacked Fanny’s commanding genius. The colony changed from the emancipation of enslaved people by working, to free love and race mixing. A doctor working on the colony published extracts from his journal which incriminated the whole colony. Word got back to Fanny. It was not long before he and an enslaved woman were living together on the colony.

In January, 1828, Fanny and a companion were able to return to Nashoba to investigate the reports. After their inspection, Fanny lost the goodwill of Memphis and the nation. She attacked conventional marriage and religion. She felt that perfect freedom equals perfect happiness and virtue. She renounced emancipation as a solution and proposed that free Black people be educated, have equal equality, and marriage with white people. She wrote, “I have always thought that if the slave question could once be settled, our free colored population would, especially in the extreme South, become gradually and easily incorporated with the white.”

She was called a bold blasphemer and a preacher of licentiousness. Soon afterwards, she married a Frenchman, chartered a ship, and sailed to Haiti with the Black people on her land. She left them on farms in Haiti and returned to America preaching reform.

Francie Mae. November 5, 2023.

Reference:

McIlwaine, Shields. 1941. Memphis. Down In Dixie. New York. EP Dutton and Company, Inc.