On Veteran’s Day this year, I was in France with a local travel group. We spent 12 days touring the country. On the second day, we visited Normandy American Cemetery and Memorial. It was a sombering experience. My late Dad and three brothers were veterans, and I am a veteran.

Many people do not know the history of Black Americans in the military. Black men could not enlist in the U.S. military until September 1940. As the war intensified in Europe, there was a need to staff up the U.S. Armed Forces. President Franklin Delano Roosevelt decided Black men could register for the draft and signed the Selective Service Act. This allowed Black men to register for the draft and join all branches of the military. Initially, they could only serve in the Army and were assigned non-combatant or laborer roles.

My Dad and maternal uncle served in the segregated U.S. Army during WWII. Dad served in Fort Huachuca, located in Arizona. This was the largest military installation for Black soldiers. At the time, the military didn’t think Black soldiers were fit for combat or leadership positions. They were mostly assigned to service or labor units and worked as cooks and mechanics. Their tasks included building roads, building ditches, and unloading supplies from truck and airplanes. The few Black men that made officer rank could only lead other Black men.

Dad wrote frequent loving and encouraging letters home to MaDear (our mother). He served with Company A 734 Military Police Battalion. In one of his letters, he enclosed a picture of him smiling proudly in his military uniform. He always wrote about his strong faith and the future he wanted for his family. In his letter dated April 26, 1943, he wrote about training to go overseas, but this did not happen. He was injured during training. He had swollen and ruptured veins in his left leg due to hiking. After an operation, he spent over seven weeks in Lukeville Station Hospital near Phoenix, Arizona.

During those times, Black military police duties included guarding prisoners and maintaining order within segregated military bases. Black Military Police could not enter restaurants where their German prisoners were eating a meal. Like many other Black soldiers after discharge, Dad returned to civilian life without G.I. benefits or a service connected disability. Uncle Earnest, my maternal uncle, did not talk about his military career. He had post-traumatic stress disorder and disappeared for many years. He never received treatment. Like millions of other Black veterans, they were treated as second-class citizens, even though they had fought in every conflict since the Revolutionary War.

The massive Allied assault on the Normandy coastline on June 6, 1944 aimed to liberate France and drive into Nazi Germany. Before dawn on June 6, three airborne divisions-the U.S. 82nd and 101st and the British 6th landed by parachute and glider behind targeted beaches. Allied naval forces, including the U.S. Coast Guard, transported assault forces across the English Channel. Beginning at 0630 hours, six U.S. British and Canadian divisions landed on Utah, Omaha, Gold, Juno and Sword Beaches. We visited Utah, Omaha, and Juno Beaches.

Approximately 1.2 million Black men served in WWII. They fought for democracy overseas while being treated like second class citizens at home in their own country. Black servicemen served in all branches of the military but were not on the frontline. They served in support roles. Overseas, many drove amphibious trucks called DUKWs. These six wheel trucks came out of the water onto the land.

On D-Day, the First Army on Omaha and Utah Beaches included about 1,700 Black soldiers. They were credited with maneuvers on the beaches in Normandy and capturing 30 major towns in France, Belgium, and Germany. The gears of troops transported across the English Channel after D-Day were moved by Black troops. These roles were crucial to helping win the war.

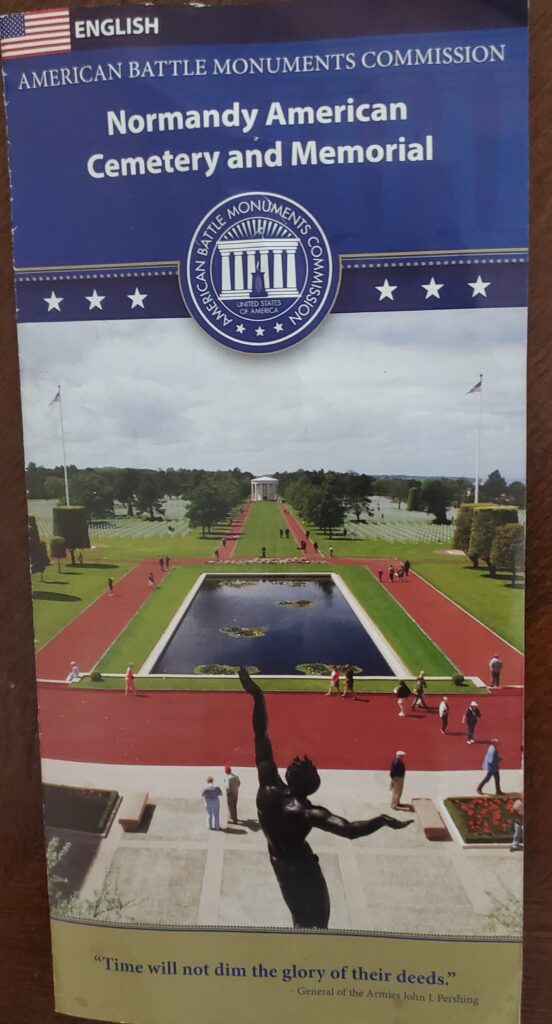

We visited the visitor center, and then took a solemn walk through Normandy American Cemetery, the final resting place of 9,388 servicemen and women. Most of the soldiers died during the D-Day landing and subsequent operations. The cemetery is one of 14 permanent American WWII cemeteries on foreign soil. Approximately 147 Black Americans, 20 Native Americans, and 4 women are buried beneath the precisely aligned headstones of white Lasa marble Latin crosses and Stars of David.

The Garden of the Missing honors those missing in action who gave their lives in this region. A bronze rosette beside a name shows that the remains were later recovered, identified and buried. Lost in thought, we walked quietly through the cemetery and gardens. We paused to honor those who gave their lives for freedom.

Overseas, Black soldiers intermingled with white people and had more freedom. Black servicemen returning home from the war found the same socioeconomic ills and racism they faced before. Despite their sacrifices overseas, they still struggled to get hired for well-paying jobs, encountered segregation, and endured targeted brutality, especially when wearing their military uniforms.

Established by Congress in 1923, The American Battle Monuments Commission(ABMC) commemorates the service, achievements, and sacrifices of all U.S. armed forces members that served overseas since 1917. Today the ABMC manages overseas military cemeteries, memorials, monuments, and markers. The majority honors those who served in WWI and WWII. Normandy American Cemetery at Omaha Beach exists to ensure that future generations remember and commemorate the sacrifice of those who fought and died on D-Day in the Normandy Campaign.

“Time will not dim the glory of their deeds.”-General of the Armies John J. Pershing

Francie Mae. November 16, 2024

References

Normandy American Cemetery and Memorial. Booklet. American Battle Monuments Commission. www.abmc.gov.January 2024.

Unsung Heroes: World War II’s Black Veterans. November 9, 2022. Bordonana, Agatha. Dartmouth. November 9, 2022. Accessed November 16, 2024.

U.S. Army. Honoring Black History World War II Service to the Nation. Pleasant, Keri, JMC Historian. February 27, 2020. Accessed November 16, 2024.